Tags

The Pepys Estate was famous, then it was infamous, now it just looks and feels like a pretty decent place to live. It was a GLC showpiece before it became (or was portrayed as) a ‘nightmare’. Its stories of crime and race and controversial regeneration can stand for a wider narrative of council housing over these years but a closer examination of their detail will take us far beyond the crude headlines. This post focuses on the Estate’s origins.

From the GLC brochure, ‘The Pepys Estate – a GLC Housing Project’ (1969): ‘‘In the foreground is a block of old people’s flats…sited close to the shopping centre. The 24-storey Daubeney Tower dominates the scene and eight storey blocks run parallel to the River Thames’ © Lewisham Local History and Archives Centre and used with their permission

We could start in 1513, the date when Henry VIII established the Chief Naval Dockyard (frequented by Samuel Pepys when Clerk to the Navy Board in the later 18th century) on the south bank of the Thames in the fishing village of Deptford. Or 1742 when it became the Naval Victualling Yard. Or 1858 when that became the Royal Victoria Yard in honour of a royal visit.

But this story – despite the rich maritime history and local heritage celebrated in the Estate’s names – begins a century later: in 1958 when the Admiralty agreed to sell the 11 acre site to the then London County Council for housing, principally for local people being displaced by the demolition of the run-down Victorian terraces which dominated the area. Clearance of the adjoining Grove Street and Windmill Lane areas created a 45 acre site on which eventually would be built around 1500 homes for a population of around 5000.

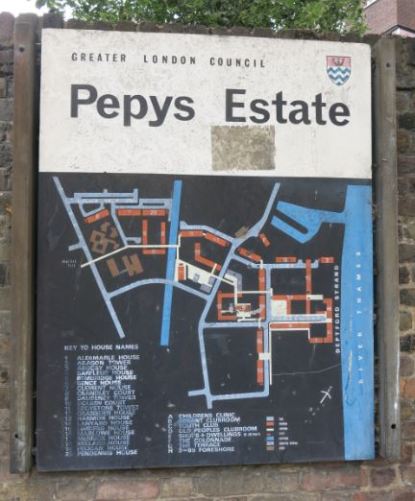

A residue of the GLC’s role in designing and constructing the Estate and a reminder of its original lay-out.

Construction began in 1966 with the new Greater London Council in charge and was completed in 1973. As housing responsibilities increasingly devolved to the new London boroughs, this was one of the GLC’s largest and most prestigious projects and, as such, it combined some of the most advanced and innovative design principles of the day.

It would be, from the outset, a community – a cradle to grave exemplar of welfare state ideals from its maternity and child welfare centre and youth club to the homes and clubroom provided for elderly people. But it represented modernity and even affluence too – both in its ‘car-free shopping centre’ and its provision for residents’ parking: one, generally below-ground, parking space to every two homes with provision for this to rise.

From the GLC brochure: ‘Many of the garages are underground or incorporated in blocks but with separate access for vehicles. Illustrated is an entrance to some garages with paved area above part of it under the block providing safe covered play areas for the use of children in wet weather’. © Lewisham Local History and Archives Centre and used with their permission

Its cutting edge, however, is best seen in its overall design. As the GLC brochure celebrating the new estate proudly proclaims, ‘in planning the estate, one of the main themes has been the separation of pedestrian from vehicular traffic’.(1) This was achieved by an extensive series of elevated walkways connecting many of the blocks. Fiona, my guide around the estate, who’s lived there since 1968, remembers you could walk from Deptford Park to the river without your feet ever touching the ground.

From the GLC brochure: ‘Part of the raised walkway system connecting the eight-storey blocks at the first floor level to the paved area around Daubeney Tower’. © Lewisham Local History and Archives Centre and used with their permission

From the GLC Brochure: the elevated shopping centre since replaced with a smaller ground-level terrace. © Lewisham Local History and Archives Centre and used with their permission

Another innovation were the so-called ‘scissors maisonettes’ – split-level flats which maximised accommodation space by reducing the internal area required for access and allowed flexible dual-aspect lay-outs to best exploit varied sites and orientations. (2) From the front door, you’d walk up (or down) one flight of stairs to the kitchen and living room and another to reach the toilet, bathroom and airing cupboard. Then, one level above or below, lay the two bedrooms and a final short flight of stairs to a fire exit.

Conversely, the Estate also reflected the emergent trend to rehabilitate, rather than demolish, older properties where they could be converted into decent homes. On the Pepys Estate, this took a particularly ambitious and imaginative form in the conversion of two former naval rum warehouses on the waterfront.

In all, 65 small flats were provided here but, at a construction cost of £3600 each (three foot thick walls didn’t make the job easy), these were always intended to be let at higher rents and their residents remained aloof from the wider estate. A sailing club, intended for local youngsters and now closed, and a branch library, still open, were also incorporated into the buildings.

From the GLC brochure,a view of the Estate from the north. The three tower blocks, Daubeney, Eddystone and Aragon, can be seen from left to right, the converted rum warehouses at the front left and the since demolished Limberg House at front centre. © Lewisham Local History and Archives Centre and used with their permission

As importantly, there was a real effort made to harness for the first time the advantages of the Estate’s magnificent location:

The barrier of industries and warehouses which has long separated Deptford from the river has been broken and amongst the features of the estate quayside gardens and a promenade along the riverwall are to be provided. Many of the new homes command fine views along the river from Tower Bridge to Greenwich Naval College including London’s dockland.

Other reminders of the site’s heritage were also acquired and converted: The Terrace, a four-storey terrace of seven Georgian homes then occupied by the Naval Film Unit and The Colonnade, two-storey buildings which formed the original entrance to the Royal Victoria Yard.

A contemporary image of The Terrace; remaining walkways linking Bembridge House and Harmon House can be seen to the rear left.

Modern construction comprised ten interconnected eight-storey blocks and three twenty-four-storey tower blocks. Here’s the ‘concrete jungle’ that some of you may be looking for but it’s worth reiterating the humanity and ideals which informed its building.

The blocks themselves were traditionally built and, beside some teething difficulties to be expected, experienced few of the problems associated with their system-built counterparts of the day. Old peoples’ dwellings were located conveniently close to the shopping centre. Larger family dwellings were placed in lower blocks with ‘as few children as possible’ to be ‘accommodated in the tower blocks’. A supervised playgroup was offered in Daubeney Tower for its children and those of the other blocks.

From the GLC Brochure: ‘For the children who do live in Daubeney Tower or nearby blocks a supervised playgroup has been organised…Even this cannot escape maritime influence’. © Lewisham Local History and Archives Centre and used with their permission

There was room to play elsewhere – ‘a large children’s area with ball court, paddling pool and other play facilities’ according to the brochure and ‘quiet green squares’ formed by ‘the grouping of the lower buildings’. In all, there were 12.5 acres of open space – almost one-third of the Estate as a whole. This was a far-cry from the densely-packed slum terraces that this scheme and others like it replaced (although it’s only fair to say that the docks nearby provided more adventurous play-space for many).

It was a popular place to move to with homes and facilities far better than those the vast majority of its new residents had previously known. Even the tower blocks which we’ve been taught to despise (unless we belong to the affluent middle class, of course, for whom they can provide the most prestigious addresses) were popular with most.

Fiona, living as a child in a corner flat on the tenth floor of Aragon Tower (next to the river), may have been luckier than most but she remembers the light and air and river views she enjoyed then which she misses to this day. We romanticise those old terraces – squalid and dirty before they ever became des res’s – and forget some of the pleasures of multi-storey living.

We’re very clever and knowing about the alleged mistakes of the past but a little humbleness is called for. We might, firstly, properly recognise the principles and care that were applied to the Estate’s planning and construction. We should acknowledge, secondly, how much was achieved. Both were rewarded in 1967 by a Civic Trust Award granted in recognition of ‘its impeccable design’.

From the GLC brochure: ‘The grouping of the lower buildings allows quiet green squares to be formed’. © Lewisham Local History and Archives Centre and used with their permission

Finally, in twenty or thirty years’ time, we can look back on the mistakes we’re currently making. Some may already be obvious. The design standards of many modern private homes (certainly those deemed most ‘affordable’) are often far below those of their past and present local authority equivalents. Other apparent mistakes will reflect a changed conventional wisdom challenging that which we take for granted today. And some will result from changing circumstances; in other words, the context and lived realities of ordinary lives which are ignored in so much of what passes as analysis of council housing.

The next post will look at what went wrong or – to be more accurate – at how far things changed and why but I’m leaving this week’s post on (no pun intended) a high note. Back in 1966, the prestige and respectability of council housing ambitions were recognised, in Deptford, by the formal opening of the Pepys Estate by Lord Mountbatten.

This red-letter day was marred for the occupants of the flat chosen for the ceremony. Charles Hayward couldn’t get time off work – he was dead busy at the Royal Arsenal Cooperative Society where he worked as an undertaker; his brother was ill with flu but, hopefully, not about to add to his workload. Charles’ wife, Florence, had to cope with the stream of visitors alone.(3)

Mountbatten dedicated the Estate to ‘the peaceful enjoyment and well-being of Londoners’. Worthy but challenging ideals in hard times, we’ll see how far they were fulfilled next week.

Sources

(1) Greater London Council, The Pepys Estate – a GLC Housing Project (1969)

(2) For more on ‘scissors’ design, please go the excellent description provided by Single Aspect who’s also written informatively on the Pepys Estate and his personal experience of living on the estate.

(3) ‘Lord Mountbatten at Deptford Home of the Navy’, South London Press, 13 July 1966

I’m very grateful to the excellent Lewisham Local History and Archive Centre for their permission to use images from the GLC brochure in their possession.

The Royal Dockyard that opened in 1513, and finally closed in 1869, was part of the site now known as Convoys Wharf immediately downriver of the Pepys Estate.

I am not sure that any housing responsibilities were ‘devolved’ from the GLC to the boroughs, as I understand it the London County Council then Greater London Council built and managed housing in parallel with the Metropolitan Boroughs then London Boroughs respectively.

One of the murkier aspects of the Greater London Council’s housing was racial segregation. When the Pepys Estate was first built tenancies were only given to white people.

Thanks, Bill. I always try to be precise and accurate and I appreciate your zeal for the same. Your point about housing responsibilities not being ‘devolved’ is perhaps a little semantic. There’s no doubt that the new enlarged boroughs assumed greater responsibilities for housing after 1965 and, in the case of the Pepys Estate, Lewisham Borough Council took over its management in 1979. Your last point is dealt with fully in next week’s post.

Bill, this is what I learned at the LMA.

http://www.singleaspect.org.uk/bro/

Thanks for that. I have taken a quick look at ss21-23 of the London Government Act, which deals with housing, and they do not adumbrate any shift in responsibilities. (An original print of the Act that contains these now repealed sections can be found on legislation.gov.uk).

Interesting, as always. You may cover this in a later post, but I had friends who lived in the now demolished lower rise blocks, they had awful layouts which rendered so much space both difficult to use and hard to heat. Daubeney by the way was one of Henry VII’s generals – responsible for the rout of the Cornish at Deptford Bridge in 1497.

Thanks and thanks for the additional insight. Not sure if your friends lived in a scissors maisonette – I’m guessing they did – but this discussion appears to confirm some of their criticisms, on the heating at least: http://www.urban75.net/forums/threads/in-praise-of-scissor-maisonette-housing.337268/

The winter cold problem was apparently Trellick and Balfron Tower only, not Pepys Estate or the scissor maisonettes there. They didn’t have any rooms directly over a corridor, they were a different design.

I wouldn’t personally describe the Goldfinger flats as scissor flats. They don’t fit the design criteria.

Pingback: The Pepys Estate, Deptford: from ‘Showcase’ to ‘Nightmare’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: The Pepys Estate, Deptford: ‘a Tale of Two Cities’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: Collage picture archive: ‘tired of London, tired of life’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: The Chinbrook Estate, Lewisham: a ‘tremendous improvement in environment and standard of living’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: SE8: I see no ships | Walking London one postcode at a time

Hi my name is Georgina Barton, I’m looking for an article in a old new paper back in Aug 1982. Regarding the Pepys estate festival where by there was a baby smiling competition. After losing my mother I found a paper cut out of this but unfortunately half of the write up is missing. And I would really like to see what the rest said to show my children. If anyone can help that would be great. I’m not sure of the news papers. That it would have been in.

Many thanks

Gina

Pingback: London’s Local Elections 2018: The Consequences of Voting – architectsforsocialhousing

I lived further up across the “border” in Rotherhithe Street. The problems of inner city decay, lack of investment and maintenance, changing population and the onslaught of the right wing propaganda machine culminating in Thatcherism in the 1980s and 1990s seemed to me unitary schemes based on civic values and public spending were doomed. As was the GLC and ILEA… the 100 year old unitary education authority for London. Look at the knife crime and gang culture now… the ILEA Youth Services went too. There is still a Youth Centre run by Lewisham but how it operates I don’t know. The top floor of Pepys Tower was converted into a very plush penthouse. I wonder who “invested” in it.?

Compared with the slum of tomorrow being built at Elephant and Castle by Landmark, the Pepys Estate, Thamesmead and other GLC projects of the 60s and 70s seem to me to be enlightened and well planned. They also recognised the need for social housing at affordable rents rather than dodgy rent and buy schemes and a private ownership approach. Needless to say with the abolition of the GLC all of the resources of the architects department, including all the plans and maintenance manuals, were destroyed too. And of course, the building inspection expertise.

If the GLC had not been deliberately dismantled for political reasons by a Conservative government hell bent on ideological warfare, Grenfell may not have taken place.

Thank you for your comment. Needless to say, I agree with it. John

Pepys tower? There was no such tower. You mean Aragon Tower now the z building. I lived in Millard House then Barfleur House. Now thankfully demolished. When we moved across Grove Street to Trinity Estate it seemed like paradise. Locals referred to Trinity as Sunset Boulevard. Childhood on Pepys was tough. Urine filled lifts, burnt foil and syringes on the stairs and regular violence. A truly horrific place. I went to school on the edge of the estate my mum was a cleaner then caretaker on the estate. The architects failed – all theory and no experience of estate life.

Pingback: Evelyn & Pepys & Deptford Dockyards – London Gardens Trust Blog

Pingback: London’s Modernist Maisonettes: ‘Going Upstairs to Bed’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: Open House London, 2022: Some Significant Housing Schemes | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: The Impact Of Our Lifestyle On Architecture – Housing Prototypes